Acting and What is Left Behind.

/When I was young somewhere under ten and above five (I don't quite recall) I was in our church’s Nativity Play. I was set to be one of the three wise men, and I don't remember much before or after, just that when I arrived on stage I could not see the north star, but rather a sea of penetrative eyes staring at me, waiting on me to “become” and I was afraid. Afraid like I never remember being afraid before. I truly don't remember much after, save for a kind of feeling I was in the middle of a tornado of hubbub when I was hauled off behind the stage with people offering all kinds of sentiments to make me feel better as I cried my eyes out. I never really looked to the stage again or thought about acting outside of the terms of just immensely enjoying spectatorship until almost 30 years later. I was always shy and in many ways I still am. I prefer the sprawling open worlds of my imagination to the itchy, hot, volatile, oppressive, and restrictive real world that I live(d) in. In the world inside my head I am an avid performer. I love being other people, stepping into the mines of the mind of another person felt like Professor X entering “Cerebro” in X-Men. In the real world I was far too afraid of people's rejection. I learned very early on that there were different planes of existence one could choose to operate on and to think about the world in that way. Finding a way to conjoin the two is the journey I still am on. Acting for me is about the two different planes, the one that lies before it, and the one on the other side of it. Once you enter into that plane which is acting, the better you are able to let go of everything that existed on that other plane behind you, the better, the more effective, the more profound you're acting is

That “truth” we speak of consistently as actors in the study of the craft is about this very idea. The thing about this “truth” is it is not a truth in the sense that it factually or realistically exists on this plane all the time. It's a truth in the sense that it is something that we all strive towards, or something that we deeply want in the most deepest reaches of our spirit. Philosopher Maurice Merleau-Ponty wrote “Our body is the general medium for having a world”. Rene Descartes be damned, the body, our bodies, simultaneously experience itself and the outside, itself and the other. The pursuit of acting and the “act” of acting is the only art so directly a portrait of this philosophy. To make sense of this compromise by interacting consciously with this “truth”, is the ideological ideal that we get to watch or “be” on stage or screen. When we are praising a performance, what we are praising is not simply craft, skill, and technique on display, but that ideological ideal of an aspect of ourselves we would love to be free enough to be. In every single movie ever made there are people doing things that people on an everyday basis never do, that for many of us are physically impossible to do. Some of those things are righteous, some are not. A great deal are necessary to a just world, and a great many are arbitrary and set up by those who are freer than the rest of us, though not free enough to not hate the idea and the possibility of someone being freer.

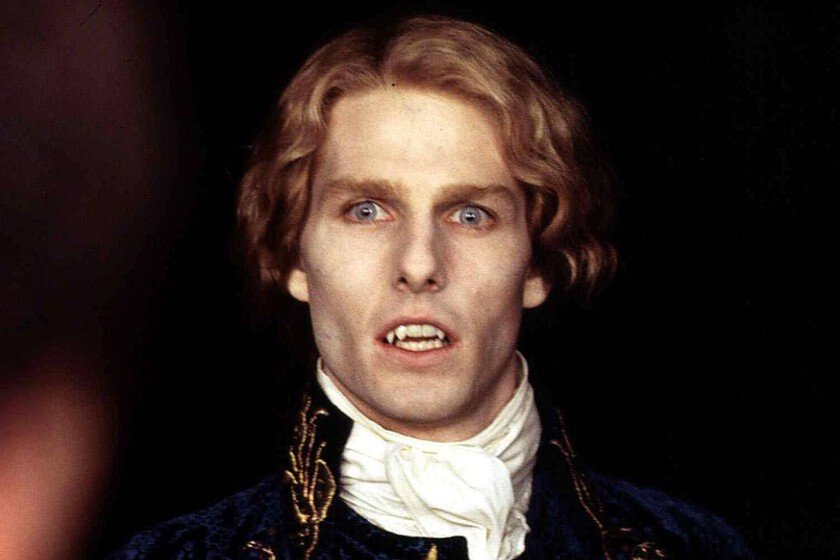

German Expressionist painter Max Beckmann once said “What I want to show in my work is the idea which hides behind so-called reality. I am seeking for the bridge which leads from the visible to the invisible.” That exact bridge should be the similar goal of actors in many respects and the “crossing” something the critic should be more interested in. Fortunately, in the world of critics there seems to be a rising tide toward exactly this recognized in praise for Jason Momoa in “Fast and Furious X”, Mia Goth in “Pearl”, or Ewan Macgregor in “Pinocchio”. Still there is far too much of a dependency on the attributes most readily associated with realism both in young actors and critics and observers. The bulk of the last several best actor Oscar winners being real life people is an example of this. Ben Affleck in “The Last Duel”, Jared Leto in “House of Gucci” (actually one of his best performances) being up for “Razzies” are in some ways examples of this. Bradley Cooper’s effort in “Maestro is an example of this. The misunderstanding of “The Method” is an example of this. The preciousness around subtlety is an example of this, the general disdain for fantasy as a genre is an example of this. Hamming, Camp, “Over-the-top” the in-and-out of favor nature of the connotation associated with these attributes, the misunderstandings, are in some respects an example of this, and why should that be? When the fantastical is such an inextricable aspect of the medium? What scares us and draws us to movies and these characters is that they are so real and yet so non-real. The “magic” of the movies could not/cannot exist without the cohabitation of these two aspects. These are real people exhibiting real emotions in completely made up circumstances, many times in completely made up places, but the make-believe of it all is more than just the material-physical reality, but that they exhibit behavior and feelings so freely in a world so free of the horde of woes that are visited upon each and every one of us several times a day everyday. In “Lethal Weapon” Danny Glover's Roger Murtaugh who at best could be pulling down 40k a year is free enough not to have to worry too much about the fact that he voluntarily drove his own car through his own living room, nevermind the damage he and Riggs (Mel Gibson) inflict on the city, nevermind the bills they have to pay on a house that seemed just a little less sizable than the “Home Alone” house. He is also free of any worries a black man living in that neighborhood might have in the 80’s and 90’s. In all of real television history have we ever seen anything like Peter Finch's monologue in Network? Just about any one chase scene in an action movie would be the news for the year, and live on infamy for years after. Hell, the OJ Bronco ride was boring as hell and lives on to this day. It is because of these existing realities and the consequences in our “real” world that most of us have never seen these things happen around us. This is a lesson to no one, but it is something that I believe important enough to remain vigilant about being cognizant of in the evaluation of both performance and in many cases movies as a whole.

We admire performance because it finds that particular “truth” of things many of us know and feel but are too afraid to say and do ourselves. That Mr. Finch did it with such reckless abandon, ferocity, and courage in the act, both in the context of the play and in the context of the “act” of playing is the source code of our infatuation. We commend the “I'm not gonna do what you all think I'm gonna do, which is just FLIP OUT!” freedom of Jerry Maguire but we're also at the same time admiring and applauding the freedom of the actor Tom Cruise to find that self that we are all so afraid of so realistically and without any sort of resistance or abandon. The “flip out” is exactly what we want most. It’s release, is what we've been waiting for since he sat down at the table and watched the smug stylings of Jay Mohr as he gaily tells Jerry he's fired. That “truth” is not so much tied to our reality as it is the truth of our collective fantasy, and the movie unconsciously and consciously acknowledges it, as does that very line in the script. You get far enough down the road considering the limitations of our senses and you understand we don't have the slightest conception of “truth” and in that sense every one of us is participating in some form of faith based upon those very limitations. This is the spiritual nature of the “act” of acting. A quick Wikipedia search defines spirituality as a religious process of reformation which aims to recover the original shape of man”. So while this may not be a religion it is a process of reformation, the thing we see when we see somebody able to come back to something resembling our original shape, something that maybe only existed (and never even fully then) when we were children. That these people (actors) are still able to hold onto that, to find that and shed the baggage of this plane to enter into one that is such an idyllic but frightful place to live in…There, in that place is the “god” of acting, proof that the nearest thing we have to utopia is the stage, the imagination of writers, vision of directors, the performance of actors and the movies. Real bodies existing on a screen within real settings surrounded by matter that we understand is part of the connective tissue that is realism. In performance it is reinforced through the tools we have available from whole disciplines and technique’s such as the “Method” or “Meisner technique” to the “magic if” and emotional recall, but it is all of it activated by imagination.

Understanding this magical aspect, this spiritual aspect over my years both in the study of acting and in the observation of it, I've become less and less invested in the realist performances. It's why so many of my favorite performances, especially recently have come from horror; Marianne Jean-Baptiste in “In Fabric”, Agathe Rousselle, and Vincent Lindon in “Titane”, or outlier movies that ask for something very specific but not necessarily real, Taylour Paige, Colman Domingo, and Riley Keough in “Zola”. Kristen Stewart in “Crimes of the Future”, Delroy Lindo’s dialogue in “Da Five Bloods” or Paul Dano’s ghastly yelling in “The Batman” these are things dancing beyond the threshold of good taste and willing to play gleefully in the other world, unshackled by self awareness and pride, or gluttonous bait for prestige. It is why Julius Carry as Sho’Nuff in “The Last Dragon” is unironically one of my favorite performances of all time. In a better world we'd understand the brilliance of what Carry found. Unfettered imagination, anchored by craft. We’d have been as interested in how he constructed this performance as Daniel Day Lewis in “My Left Foot” or “There Will Be Blood”. We’d ask the “how”, “why”, and “what” of a concoction thrust into a proud lineage of performance that includes anyone from Gloria Swanson in “Sunset Boulevard” to Peter Lorre in “Mad Love”, and then beyond him and from him Samuel L. Jackson in “Pulp Fiction”. For Carry to climb into jumper pants, shoulder pads, a Jheri curl wig, and Converse with polarized shades on, entering every room like a superstar pro wrestler is at its core the soul of acting. It's leaving behind this plane for another, smashing together and stitching the real and the very unreal. In reverse the anchored and oppressive reality in Joaquin Phoenix’s performance as The Joker in “Joker” is something I dislike. The script and the banal intention of the movie suppresses the inherent absurdity of the existence of the Joker. Misses almost totally the opportunity to allow Joaquin Phoenix the ability to play with his considerable toolbox and construct something never before seen, rather than what already exists whether in regards to the sociological implications or the “King of Comedy” reference. Using fully ones imagination, besides the public speaking aspect of it, for every fresh actor is the hardest fear to get rid of. The most difficult aspect to shed is the safety of “normal” and “real” and it never stops living with you, fighting you,it is always there. The “how far they're willing to go into this plane of existence” is one of, if not the defining quality of what separates the tiers of actors. It is the profound awe behind watching a Benedict Cumberbatch crawl around on all fours in a skin tight suit with a bunch of little funny balls on it and snarl and growl as if he is a real dragon, something that has never existed. The creation and committed execution of this thing that in any other place would be considered so absurd that you might be committed, especially if you did it on multiple occasions- which is what actors do. I feel one of the reasons why comedians usually make such good actors is due to the built-in nature of the willingness to forego any ideas of things like embarrassment and shame in comedy, which in many ways (both productive and unproductive) have to do with harnessing behavior into rigid categories. So absolutely the guy who was willing to get down to his skivvies and run around pretending he's on fire screaming “Help me Tom Cruise!” with the attachment to the very real reality of body shaming/shame or guardedness completely left behind, of course that guy was probably going to turn out to be a pretty good actor.

“If you speak any lines, or do anything, mechanically, without fully realizing who you are, where you came from, why, what you want, where you are going, and what you will do when you get there, you will be acting without imagination. That time, whether it will be short or long, will be unreal, and you will be nothing more than a wound-up machine, an automation”-Konstantin Stanislavski, “An Actor Prepares”